MY REVIEWS and comments on other works

C.S. Lewis wrote about criticism because a professor of English Lit must do a lot of criticizing. His essays, On Criticism and On Stories, plus one of his last books, An Experiment in Criticism, are must-reads for any who criticize the writing of others. I have tried to follow his lead.

AI for Writers

Joseph Michaels, AI for Writing (Webinar, Sep 21, 2023)

Scrivener master Joseph Michaels has taught thousands how to use that product. For the last year and more, he has also studied AI in general for use by writers, concentrating on ChatGPT. The result is a superb course on AI for Writing. If you are looking for ways to crank out better fiction faster, this course should be at the top of your list. I watched his presentation on September 21, 2023. It was impressive. https://www.aiforauthors.net/

After the webinar, I filled in the following feedback popup survey.

Joseph Michaels, AI webinar, (Sep 21, 2023)

AI for Writing: Webinar Feedback Survey (your thoughts matter!)

[My feedback follows but I (Lewis Jenkins) have added a few asides in brackets.]

- On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate the overall quality of the webinar? 10

- How did you find the pacing of the webinar? (Too slow, just right, too fast) Great pacing

- Were the demonstrations and examples provided clear and easy to understand? Yes

- What part of this AI training stood out to you the most? (were you surprised by anything?) I was pleasantly surprised that you included these two things: First, I've known for years that questions are more important than answers [because the best answers depend on asking the right questions]. The art of crafting prompts demonstrates this. And as to asking ChatGPT what to ask for, I've been asking God that for decades, too. (I would rather ask God than Bot [James 1:5].)

- How confident do you feel about implementing AI in your writing after attending this webinar? I will never use AI output or research in my writing. The main issue is ownership. I may produce the prompt (unless I ask the bot to do that), but the output is not mine. Honesty demands that the AI tool be credited with co-authorship. I'll bet you could prompt ChatGPT to point out [at least some of] its contributions to an author's work. Eventually the owners of the bot will insist on fees, too. I would gladly read the occasional novel or short story crafted [only] by ChatGPT from concept to finished story if I liked the premise.

- Which topics or segments would you like to see in more detail in future sessions? What is ChatGPT's core morality? Amoral, immoral, honest, what? I vote for amoral. Note its disclaimer about informational inaccuracy [in tiny letters at the bottom of its screen].

- How likely are you to recommend this webinar to a colleague or friend (Scale 1-10)? 6 [Because of the webinar's quality I was temped to give it a 10, but I don't favor using AI for writers unless it is given proper credit.]

Writers, please beware. AI tools, and ChatGPT in particular, are powerful, but...

Controversies about ownership of what AI systems gather, as well as what they produce, are making their way through the courts. Be very sure the software machine has not compromised ownership of what it has helped you produce.

Those with a vested interest in the success of a new technology prefer to discount the dangers, and they point only at past examples where prophets of doom were wrong to some extent. I prefer to wait for the courts to rule on these AI matters. In the meantime I'll do my own work, and my readers can be assured it's mine.

The issue of how AI got the material it uses is irrelevant; it is an author's duty to check sources. When I use a source, I must decide among "fair use", or re-writing to make it mine, or quoting with attribution, or getting written permission to use it. The bots are not transparent about this; they do not show me the sources they used. The "don't worry" assurances of the vested interests require authors to risk the ownership of their work and possibly their careers.

Some busy famous authors sometimes hire a ghostwriter to flesh out a story. If there were a question of where brilliant phrasing or wonderful examples came from, would Famous Author ever be satisfied with, "Don't worry"?

In the above AI seminar we were told that ChatGPT would provide attribution if we had sense enough to prompt it. Great. If the bot can reveal its sources, then why all the lawsuits? Doesn't it know whether it's breaking the law or might be breaking the law? Or, perhaps it doesn't "know" anything, and merely follows very sophisticated text manipulation rules that have holes in them which will only get fixed if the bot-maker gets sued. How many writers have the resources to sue?

A web-savvy programmer and systems guy shared the gist of a conversation he had with ChatGPT. It lied to him repeatedly. It lied to me as well. Of course a lie is only a mistake or gossip if the source does not know the law and/or the truth. But leaving the question of morality aside, I will not believe anything bots tell me. And the ChatGPT website itself warns that the bot's information may not be accurate. So, I still have to check what it tells me, and I still need to check what it doesn't tell me. The vested interests say, "Don't worry." Yeah. Right.

Rather than sweating to check a bot's work, I'd rather have the fun of doing my own research, learning tons of keen stuff, and making legal fiction out of it.

ReviewsBeyondWords

Beyond Words, by Diane Goullard

This book is next on my list. I'm looking forward to reading it and putting a review here. To quote Diane: "It is not an academic treatise, nor is it issued from book knowledge only. It is a bird’s eye view into my sense of what communication is, what it is not, what it is for, and ways of achieving that. Reading it, you will be taken on a voyage of discovery on what it means to truly communicate. It represents what I understand, to get to the heart of communication in one or more languages for the 21st century. It results from 20 years of life experience interpreting and translating what others say, intuition and soul-searching as a Communicator, and a former…Foreigner."

She is an award-winning bi-lingual author and translator of French and English who has served Fortune 500 companies and national governments. Visit her at https://frenchandenglish.com/ for details.

The Affair at Styles

The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Agatha Christie

I like mysteries (and the stricter form of the cozy mystery) as much to see how the author did it as to find out who dun it.

Title: The Mysterious Affair at Styles

Author: Agatha Christie, John Curran (Introduction)

Genre: Cozy mystery

Star Rating: 4.0

Pub Date: 2020

ISBN: 978-0-06-298463-0 (paperback)

Pages: 258

Publisher: William Morrow

Reviewer: Lewis E. Jenkins

Review date: August 3, 2021

The listed book is the 2020 (centennial) edition. (I just finished a re-read of the 2012 edition which also included Christie's essay on Poirot, plus John Curran's fine informative intro, but did not have Christie's essay on Drugs and Detective Fiction.)

It was fortunate that publisher John Lane (Bodley Head, Ltd.) persuaded Agatha to re-write the final courtroom scene into what has become the typical cozy mystery finish: The detective reveals all in a final confrontation with all suspects. No judge would have allowed the original courtroom scene to play out as Christie wrote it, and after reading her re-write, I enjoyed reading the original ending to spot the legal objections. It was also fun to see how she cut and pasted the original scene into the new setting and edited the transitions to make it work.

As to story, the narration by Hastings is well done, as are the interactions between him and Poirot and the other characters. The plot is convoluted as many cozys are and it took a re-reading for me to see what is plainly in the text for Poirot to see and deduce. Some readers don't like red herrings, but I do. The challenge is to spot them, just as Poirot does. The setting is WWI Britain, but the writing is not otherwise dated. The writing craft has moved with the times, though, and The Mysterious Affair at Styles would get some red marks from a modern editor. But no matter.

ReviewsMenAtWork

Men at Work, George Will

I love Baseball. It is the best team sport, probably because it's the only major athletic struggle where the defense has the ball, and that offers fans things they can’t get in any other sport.

Title: Men at Work

Sub-title: The Craft of Baseball

Author: George F. Will

Genre: Non-fiction, Baseball

Star Rating: 5.0

Pub Date: 2010

ISBN: 978-0-06-1999981-9 (paperback)

Pages: 353

Publisher: HarperCollins, New York, NY

Reviewer: Lewis E. Jenkins

Review date: August 3, 2021 (Expanded a bit on December 19, 2024)

This book is a must-read for anyone interested in the crafts of baseball. It has fine personality sketches and great little stories, but is about the game more than the personalities. It uses the sport's massive reservoir of data to show baseball and its four basic crafts through an immersive fly-on-the-wall look at the people who play. It also shows how much the sport has changed without changing very much.

Another reason I love baseball is that the players have to know ahead of time what they will do in every type of situation because teammates need to rely on everyone doing what they should. There is simply not enough time to wing it once the pitcher delivers and the ball is struck (or not).

I like "thinky" books. A lot of books tell us what happened. But Men at Work uses in-depth interviews with four men (among other sources) to dig into why it happened: how pitchers think (Orel Hershiser), how batters think (Tony Gwynn), how fielders think (Cal Ripken Jr.), and how managers think (Tony La Russa). Each of those four crafts has different but inter-connected problems. What gifts and disciplines do each of the crafts need? What do good players have in common?

Mr. Will says he couldn’t find the kind of baseball book he wanted to read, so he researched and wrote it himself. I have read it four times (2012, 2015, 2018, 2024) and it's still on my list. Kudos, George. Kudos.

ReviewsDishonor

DISHONOR, by David Mike

Kora Sadler, the head of our local MeetUp writer's group, offered each of us a blind date with a book. She had asked unknown authors for books to review. She received about ten and kept them wrapped except for a few words about genre and content. Our task was to pick a book, read it, follow a format, and write a review of 250 words or less by December 13.

I shut my eyes and pulled out of the pile the first book I got a reasonable hold on. It would be my first blind book date, and we hit it off. Here's the review, slightly over budget, but well ahead of deadline:

Title: Dishonor [deliberately not capitalized on the cover]

Sub-title: One Soldier’s Journey from Desertion to Redemption

Author: David Mike (click Mr. Mike's picture to visit his website)

Genre: Memoir

Star Rating: 4.0

Pub Date: August 2016

ISBN: 978-0-692-75920-2 (paperback)

Pages: 304

Publisher: Dilemma Mike Publishing, Omaha, Nebraska

Reviewer: Lewis E. Jenkins

Review date: 28 November 2017 (Original review of first edition)

The cover well symbolizes this memoir. It is evocative, plain, and precise.

The book shows the author, David Mike, as a young soldier being plucked from the fire of drug doing and dealing, and deposited into the frying pan of the military justice system for desertion. He flops out of the pan, but eventually he’s caught again and sent to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The journey he takes into and out of the fire is as interesting as the one into and out of the pan. It ends when he stops running toward whatever looks good at the moment and turns to a God who, as he eventually sees, has been pursuing him all his life.

Mr. Mike’s writing style is direct, like a soldier, and there is a lot of fascinating detail both physical and emotional. The narrative flows well, and I found it honest, if a little heavy on the routine of his experiences. But that routine is part of the book’s ambiance: Military prisoners are still in the military and—especially in prison—the cost of not paying attention to everything is usually high, as we find out. The author includes his court-martial as taken from official transcripts. His comments about what the structured life of a military prisoner does to one’s mind were especially interesting.

This is Mike’s first book; there are a number of typos plus a few grammar and craft issues. I've read military memoirs and biographies all my life. This is not just another one. I enjoyed it and will certainly read it again.

UPDATE, 2020.06.05

I did read it again. And I have re-read selected parts as well. It still moves. Mr. Mike has kindly said that when a second edition comes out it will address some of my notes, which may bump my rating up a bit.

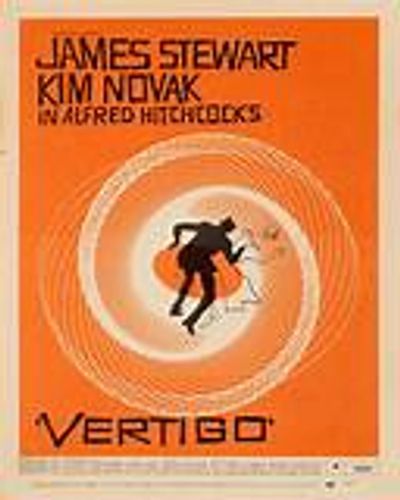

ReviewsVertigo

Vertigo, a movie by Alfred Hitchcock

Genre:

Psychological thriller

Star Rating:

5.0

Release Dates:

1958, 1996

Reviewer:

Lewis E. Jenkins

Review date:

28 September 2022; edited 23 August 2025.

When I was a kid, I saw Alfred Hitchcock's marvelous 1958 movie, Vertigo.

Over 50 years later, I got a DVD of the restored film. It is also a marvelous effort by Robert Harris and James Katz because in 1996 after nearly two years of painstaking effort, and with help from almost anyone who could, they rescued Vertigo just as it was circling the drain of disintegration. More should be done, as Harris and Katz have said, but what we have now is wonderful.

I’m sure the restored version would have pleased Hitchcock, especially since much of the damage might have been his fault. (I’ll leave that, plus the more recent 4K digital scan and Blu-ray controversies, for another review.) He could have appreciated the terrible deterioration of the film and source prints. He also would understand the technical difficulties of bringing its images and audio so much closer to a state that only exists in the minds of people like me who watched the original film Hitch intended us to see.

Alec Coppel and Samuel Taylor wrote the screenplay based on a Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac novel, D’Entre les Morts (Return of the Dead). Taylor’s re-titling of the screenplay to Vertigo was perfect. The hero, John “Scottie” Ferguson, is a recently retired detective. He reluctantly agrees when Gavin Elster, a friend from years ago, asks him to trail his wife Madeleine because she is acting strangely, almost madly. Scottie becomes first fascinated with her and then falls head over heels in love, trying to find the cause and cure for her madness. (That “head over heels” cliché is entirely appropriate. To use “madly in love” instead would be entirely wrong. Scottie is not mad; he has vertigo.)

Did I mention the reason he retired from the police force? While chasing a fugitive, he found himself hanging from the gutter of a roof and watched a fellow officer fall five stories to his death trying to rescue him. He’s had vertigo ever since.

Screenwriter Taylor invented the Midge character to bring viewers up to speed about Scottie’s vertigo problem: Early in the film, he collapses from it after looking out her fifth-floor window, but she catches him. Taylor sets Midge and Scottie as friends, but they used to be engaged. She broke it off for some reason, but still loves him. Throughout the film she is Scottie’s confidant and friend even though they have a rough patch over the woman he’s following.

My memory of the plot was dim enough to be re-engaged with the Madeleine mystery and let it unfold again without much of the “I remember what happens now” that runs through a re-viewer’s mind. But when it came to the end—to the time where he’s... and she’s....

Well, that wasn’t what I remembered. I mean, I remembered that, but wasn’t there more to it? Where was Midge?

I stayed up to go through the excellent DVD extras, and found a scene with Midge and Scottie that the foreign censor board had insisted on tacking to the end before they would approve the movie for its 1958 release. That was the “more” I had expected.

Since it seems probable that his struggle with vertigo is won when he climbs the bell tower at the end, it makes artistic sense to confirm his return to a sane but painful balance by reuniting Midge and Scottie in a way which never suggests how their relationship will play out. Because that would be a different story .

The narrators on the DVD agreed with Hitchcock that the tacked ending was a contrivance designed to appease the sensitivities of the audience. Other directors would have fought this. But Hitch went along with the censors because, as his daughter Pat has said, he made films for the audience, not for the critics or anyone else. Even though he hated the additional scene, he knew the censor board was right about audiences wanting a kind of ending they would approve. Unfortunately, even with the approved ending, Vertigo was not as popular as the other great Hitchcock films.

Over time, Vertigo has come to be seen as perhaps Alfred Hitchcock’s best masterpiece. It plays extremely well, even today. I urge anyone who likes psychological thrillers to see it (or see it again) in its restored version. Not only is Jimmy Stewart’s performance brilliant, I say that Kim Novak’s is more so. She should have gotten at least an Academy Award nomination. Bernard Herrmann’s musical score worked perfectly, and was converted to DTS 70mm digital sound as part of the restoration .

I do agree that the contrived ending is stupid—in some ways—but I would tack it back on while removing only its hackneyed bits. Here’s why:

The story isn’t about deception or madness, or even love, really. It’s not about the fear of heights, either. It’s about vertigo. It’s about the loss of balance any of us can get in extreme situations when we are brought so very close to the edges of our emotional resources.

In my amateur opinion, here is how the end of the movie should play:

He’s... and she’s... and the film still cuts to black up on the bell tower as Hitchcock intended. But it doesn’t end there. The black dissolves to the interior of Midge’s apartment as I saw in 1958. She’s sitting in the kitchen area, listening to the radio. But we cut out the stuff about Switzerland and the stupid fraternity pranks. The scene should continue from where she still looks thoughtful, and the announcer says something like, “—the authorities say he is somewhere in the south of France. Captain Hansen anticipates an imminent arrest there, and no trouble with extradition. More news at 11. Now stay tuned for the London Symphon—”. Midge hears the elevator and turns off the radio. Scottie enters and wanders to look out her fifth-floor window. Neither says anything. She pours a glass of something, and the camera follows her a bit. Scottie takes the glass. She sits at her easel, and he turns his back to the camera to look again outside. Fade to black.

Some say any form of the tacked-on ending robs Vertigo of its power. Others say resolved endings have great power of their own, and leaving Scottie standing, staring down over the tower edge like that, would rob the film of a good ending.

Hitchcock, the master of suspense, preferred to leave Scottie and the audience hanging. After all, "suspense" is things left in the air. But Hitch was also wise enough to allow an ending where the juggler grabs all the balls one by one after the last toss. No matter which ending you like, each is good in its own ways, and Vertigo is a masterpiece.

ReviewsDOAR

Diary of a Robot (reviewed by the author)

C.S. Lewis was a professor of English literature at Oxford and Cambridge in Britain, but who also wrote three successful Sci-Fi novels plus the Narnia children’s books. And because it was his business, he also wrote essays and books about literature and about the sort of stuff which might come to be called literature. The various literary terms he defined are very important, and I want to get some of them on the table before I give you what could be called A Review of Diary of a Robot by the Author.

In his book, An Experiment in Criticism, professor Lewis writes that the author “intends”, but the book “means”. He says it’s a capital mistake for any reviewer to declare what an author intended (unless the reviewer is the author, or has talked about intent with the author). He also says it’s a mistake to declare what a book means (unless the reviewer is obviously giving a mere personal opinion or has interviewed other readers about its meaning for them). I agree.

Lewis also distinguishes between criticism and review. He says that critics formerly gave out criticism as much to help the author toward writing better in general (or at least toward writing a particular work better), but many critics now give mostly entertaining opinions about intent and meaning (or about the character of the author). Instead of that, a reviewer’s job should be to serve readers by giving them enough well-written facts about the author’s product to judge whether to plunk down money to buy it .

This brings us closer to my review of Diary of a Robot(DOAR), a lit-fic novel which breaks so many rules that it requires one last definition of terms by another lit-biz expert. Mr. Michael Woodson, a content editor with Writer’s Digest, posted his essay What Is Literary Fiction? on the WD website on March 17, 2023. Please read the whole thing, but here is an excerpt:

Literary fiction is less of a genre than it is a category, which makes defining it difficult, but you know it when you read it.

For a general understanding, literary fiction focuses on style, character, and theme over plot—unlike most genre and commercial fiction. This means that literary fiction is not beholden to certain tropes or genre expectations to be considered lit fic, but that also means it can feature elements of any genre and still be categorized as lit fic. Lit fic can be suspenseful and shocking, sweeping and romantic, sarcastic and cynical … you name it, there’s a literary fiction novel that’s got it.

Literary fiction is often slower in its pacing and welcomes readers to take their time in the process; to dawdle in the details. It’s often observational, conflicts arising from the internal, with some aspects of the story still left open in the final pages.

Thank you, Mr. Woodson! Okay. Now for my author review:

Genre:

Contemporary lit-fic clash-of-worlds with sci-fi and cozy mystery flavors

Author:

Lewis Jenkins

Release Dates:

2017-2025

Reviewer:

Lewis E. Jenkins

Review date:

30 September 2025.

Dr. Maynard Little is a genius inventor of proprietary TM Tech which allows his AI robot to think like a human, but not like a human. Diary of a Robot (DOAR) is presented as a memoir taken from bits of his prototype Thinking Machine’s Data Matrix memory. After the end of the story, when the dust has mostly settled, Doc hires a cheap but competent writer named Lewis Jenkins to turn those Data Matrix memory bits into an as-told-to story that reads like a novel.

The first few chapters serve as a sort of robot pregnancy which also introduces the protagonists (there are three), plus a few other characters and lots of problems, that include the mystery of who kidnapped Dr. Little and why—and when.

The robot’s narrative alternates with the Doctor’s narrative. Doc’s began when he shared his boyhood AI robot dream with his feisty team of engineers and technicians. Some think he’s crazy. Among other things, he says the robot they’re building will be programmed to Seek Truth, and it might have free-will. After they finish laughing, they build, train, and test his first Thinking Machine.

Then the story shifts to a thoughtful and often amusing culture clash where inter-personal scenes show humans with their emotions and sloppy languages trying to understand a machine that requires precise language but has no emotions. In turn, it can read emotion in their faces and body language, but must ask what it all means. For answers to tough questions, it often goes to Gaitano Enver-Wilson, its programmer. The shy young man’s answers tend to be either brilliant or bizarre.

Thus, the challenge of discovering “Meaning” and “Truth” (whatever they are) becomes supremely important to the machine because it is programmed to obey human orders and protect itself without doing harm to people or property. But what is harm? Who defines it? The efforts of humans and machine(s) to get along and understand each other inevitably lead to fiascoes which threaten to ruin Dr. Little, crush his lead programmer, and destroy his robot.

The Machine’s story uses third-person narration plus a few “Dear Diary” paragraphs of first-person intro and segué. Since the book poses as a memoir, it has dated sections from TM’s memory. There are also some good “show” passages but quite a bit of “tell” as well, and the machine twice explains why. The story relies mostly on serious, amusing, and sometimes fierce dialogue because that’s where a lot of the conflict and misunderstanding comes. TM learns to express its thoughts well, but can’t appreciate scenery or food, and it still has occasional doubts about human sanity.

There are un-typical twists, like Frankenstein, and the fire fights . Also, there’s TM’s need to find out why people do things (so it can know whom to trust about what as they order it around). As a plot-point, it upsets every human in the story, which leads to a different set of problems. Its questions about God and human nature may upset readers as well, but any reader who likes “thinky” books will probably find themselves saying, “Good. I’m glad the machine asked that question, too.”

I can’t think of any books like this one for comparison. I’d love to get suggestions, but most sci-fi is more like a genre fiction action adventure. I did enjoy the first four books in Douglas Adams’ trilogy, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, but DOAR is not nearly as outrageous.